I read Atomic Habits at the end of last year and I’ve been meaning to talk about it for a while. It’s lived at the back of my mind since I did read it and not necessarily in a good way, it’s more of an irritation I can’t shake. The podcast If Books Could Kill just dropped an episode on it, which has prompted me to finally write out my thoughts on this.

I had a general awareness that this books exists from seeing it in Waterstone’s displays. I think I had picked it up to read its back cover, and then put it down and forgot all about it. Then last year I started watching video tutorials on note-taking using Obsidian.mb, it seemed like everybody had read this thing, and my curiosity was piqued! [1]

At the time I really wanted to make more time in my day to work on writing and blogging. As an adult person with a full-time job it is very hard to find time in the day for maintaining a clean house, garden, relationships, eating healthy, exercise, and sleep; never mind for anything else. I thought maybe if I could get a bit more structured routine into my week I can carve out some more “free” time for creativity.

The Good Habit I need is to do my workouts in the morning before work. After work just does not work for me – I’m too tired and hungry, and I just want to do something I enjoy. I also find (once I get going) that I have more energy for cardio first thing, and it makes me feel a lot better during the day.

I’ve been getting stuck in the Bad Habit of not getting out of bed when my alarm wakes me up, and staying there either scrolling on my phone or – honestly just daydreaming – until about 5 minutes before I’m to log on for work! I’d still go for a walk at lunchtime and after work (weather permitting) but not doing strength and cardio workouts leaves me feeling grotty and stiff (and also see: Reasons Why I Should Get Up & Do Some Exercise).

What are Atomic Habits?

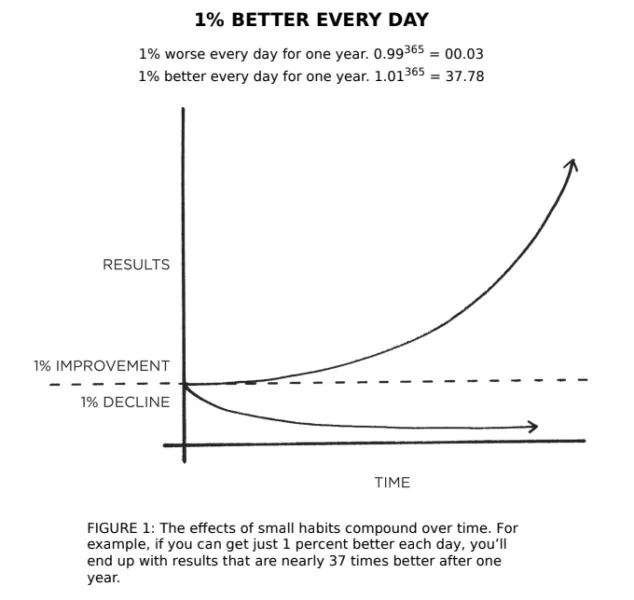

The title can be a little misleading. In this context, “atomic” refers to tiny components that combine to create something powerful. James Clear’s whole argument is that small, consistent habits—stacked together over time—can reshape your entire life. The productivity world online has really embraced the term, with phrases like “Atomic Essays” popping up everywhere, so if you’re immersed in that space, the title probably feels familiar. But coming into it without that background (or without a strong science brain like some people!), the name can definitely feel a bit confusing at first.

Who is James Clear?

One thing that struck me while reading the book is that James Clear isn’t actually trained or accredited in anything related to psychology, behaviour, or habit formation. He’s essentially just a guy on the internet with a very successful blog and newsletter — and that success seems to be his main credential. He’s branded himself as “an expert on habits and decision-making,” but what does that title even amount to in practical terms? It certainly doesn’t translate into the ability to write a genuinely helpful book.

What really surprised me in the introduction is how he portrays himself: extremely organised, naturally disciplined, and someone who finds it easy to build positive habits. That completely threw me off. How is someone who has always operated that way — someone whose brain seems wired for routine — supposed to relate to people like me? People who have spent their entire lives struggling to maintain habits for more than a few weeks? If he’s never had to fight for consistency, how can he claim to guide those of us who do?

The fact that he believes those experiences make him qualified to give habit advice immediately raised red flags for me. It felt like he was gearing up to say, “Just do what I do,” without recognising why that’s hard for people who aren’t naturally disciplined. Honestly, I’d much rather hear from someone who’s naturally messy or disorganised but managed to stick to a routine for a year — that person would feel far more relatable and credible to me.

He also starts the book with a story about getting hit in the face with a baseball, which has nothing to do with habits or expertise. It just felt random, like he included it because it’s the only dramatic thing that’s ever happened to him.

Why is this a book?

The whole book reads like what it originally was: a long blog post or newsletter dressed up as a bestseller.

It’s also obvious that it was written by someone who has never genuinely struggled with habits. The tone is flat and mechanical, the wording feels recycled over and over, and the pages are padded with charts that add nothing. Honestly, the core message could be condensed into a single sheet of paper — but that’s my complaint about most self-help books anyway.

On top of that, he constantly pushes readers to visit his website and hand over their email for extra “resources.” He mentions his site sixteen times. By the fifth reminder, it stopped feeling helpful and started feeling like he thought I was stupid — or worse, like the whole thing was edging into scam territory.

Are Atomic Habits useful?

There are a few genuinely helpful ideas in the book, but none of them warrant a full-length manuscript. At best, the core content could fit into a long blog post. Because there isn’t enough substance to justify a book, the rest feels like filler — sometimes meaningless, sometimes drifting into pseudoscience.

Many of the examples he uses to “prove” his theories are either stretched beyond recognition, cherry-picked to fit his narrative, or based solely on personal anecdotes. In one case, it’s literally an anecdote of someone else’s anecdote. He even cites Twitter and Reddit threads as if they’re credible sources. Skimming Reddit does not count as research, certainly not in a book that’s been prominently displayed in every bookshop for years.

Another major issue is how he lumps completely different behaviours under the same “habit” category and treats them as equally fixable. He puts things like binge-eating junk food, scrolling social media, weightlifting, voting, learning a language, giving employee praise, making your bed, and even compulsive nail-biting on the same level. But these are not the same kinds of behaviours. Some are lifestyle preferences, some are tied to personality, some are compulsions, and some relate to mental health. They do not share a single, simple solution.

While he does make some worthwhile points about creating routines, stretching those ideas across every area of life results in a muddled, overly simplistic message. And honestly, it’s no surprise — he hasn’t done any rigorous research, nor is he trained in psychology. He’s essentially offering advice based on a handful of articles, social media posts, and a couple of books he’s read.

James Clear’s Four Laws

The entire book essentially revolves around James Clear’s “4 Laws of Behavior Change.” That’s it — that’s the whole framework, and really the only information you need from the book.

1. Make it obvious (cue)

Use clear triggers to remind yourself when to do a habit—like linking it to a specific time, place, or action. He also promotes “habit stacking,” where one habit naturally follows another.

2. Make it attractive (craving)

Pair the habit you want to build with something you already enjoy, so the good habit feels more rewarding.

3. Make it easy (response)

Shape your environment so the good habits are effortless and the bad ones are inconvenient. And keep habits tiny at first — ideally something you can do in under two minutes.

4. Make it satisfying (reward)

Track your habits to create a sense of progress and give yourself a small reward loop.

Build a routine by chaining good habits

The most useful takeaway I got from Atomic Habits was the idea of cues, or what Clear calls “Habit Stacking.” Essentially, it’s about chaining small actions together so that one good habit naturally leads to the next. I also liked thinking of each step as its own tiny, easy-to-complete habit.

Here’s how it looks in my morning routine:

- My alarm clock on the other side of the room goes off at 7am.

- This triggers me to have to get up out of bed to turn it off.

- That is then my cue to go to the bathroom for my morning pee.

- After peeing and washing my hands at the sink I immediately brush my teeth.

- Then I put some music on my phone while I put on my gym clothes because that helps me get in the mood to exercise.

- Gym clothes on are my cue to go to and get out my exercise mat.

- Once I’m on my exercise mat I then do a workout.

This framework really helped me with the first few steps — especially brushing my teeth. I now do it automatically right after using the bathroom instead of waiting until after breakfast. Working from home, I used to sometimes forget until much later in the day — gross, I know!

Steps five through seven — putting on music, getting gym clothes, doing the workout — required more effort and motivation. They worked for a few weeks, but this is where I started running into some of the book’s limitations.

This framework was a useful tool for rethinking my habits, and it worked well for the first few steps—specifically, getting me to brush my teeth consistently. I trained myself to do it right after my morning pee, which eliminated the problem of forgetting later on because I now eat breakfast at my desk while working from home.

Where the system started to break down for me was with the subsequent steps, which required more active effort and motivation. I followed them, but only for a short period before falling off track. This is the juncture at which I find the advice less sustainable and start to see its limitations.

The hormone rollercoaster

It becomes clear that this book was written from a male perspective, or at least by someone who doesn’t experience a menstrual cycle. The advice is heavily centred on food and exercise, with a strong emphasis on daily, unvarying consistency.

The core tip to “Make it satisfying” involves using habit trackers and the “don’t break the chain” method. While this works for simple actions like brushing your teeth, it’s less practical for habits that depend on complex physical or mental effort. For those of us with menstrual cycles, our need for food, ability to focus, and energy levels fluctuate dramatically every few weeks. Maintaining a rigid, identical routine is not always possible—or even healthy.

In my case, my energy plummets around my period. I’ve learned that forcing myself to get up for daily cardio during that time is counterproductive, leaving me exhausted for the following week. Thanks to insights from Period Power, I’ve proven that it’s far better for me to lean into that fatigue for the few days I feel bone-tired, taking a complete break from everything I can—exercise, chores, and demanding mental tasks. When I honour this need, my energy rebounds much more quickly.

However, if I were keeping a habit tracker for morning workouts, rewarding myself only for an unbroken chain, then every 28 days my necessary physical break would “break the chain.” This would make me feel like a failure, on top of the other self-esteem challenges that come with hormonal shifts.

These cyclical fluctuations in hormones, energy, and focus are a primary reason I struggle with rigid routines. I’ve never been able to maintain a consistent exercise regimen or even use a habit tracker for more than a month, as my motivations are constantly reshaped by my cycle. This is a challenge James Clear’s framework cannot address, and based on the book’s content, it’s a reality he doesn’t seem to comprehend.

Having read Period Power after Atomic Habits, I now track my cycle and strive to work with my body’s changing needs in each phase. This approach has led me to feel generally happier and healthier. The current challenge, however, is figuring out how to rebuild a sustainable morning routine that accommodates this cycle after my recent house move.

Caution if you have an eating disorder

The book offers what I consider irresponsible advice on food and diet, particularly concerning weight loss and fitness. Strategies that encourage hyper-focusing on eating, maintaining detailed food logs, and concentrating on the negative feelings after a binge could be highly triggering for anyone with a history of eating disorders.

Edit, Jan 2024: Upon reflection, I’ve realized a core reason for my frustration. While the book isn’t exclusively about exercise, it heavily buys into the most unhelpful aspects of diet and fitness culture—specifically, the “no pain, no gain” and “all-or-nothing” mindset. I was seeking a framework to help me form sustainable habits and reap the genuine benefits of exercise, without the layer of guilt and shame that mainstream fitness culture often promotes, which typically leads to an unproductive cycle.

Edit, March 2025: I’m happy to report that I have since “cracked the code” on self-motivation and maintaining better habits, especially for exercise. I plan to write a follow-up on my approach, but as it’s a busy time, don’t hold your breath for its immediate release

So, who is Atomic Habits for?

If you’re someone like James Clear, who possesses a great deal of self-discipline and finds personal organization inherently rewarding, you will probably enjoy this book. However, you also likely don’t need it, as this type of structure comes naturally to you.

Conversely, people who genuinely struggle with habit formation will probably find little long-term value here. Like many mass-market self-help books, it remains too vague to offer the specific, individualized advice that makes a real difference.

My main takeaways were to make habits small and easy and to stack them into a routine. This advice is neither new nor revolutionary. I’ve always known that I need to lower the barrier to entry for my tasks, and there are areas, like writing for my blog, where I still need to apply that principle. Reading this book served as a reminder framed in a new structure, but I didn’t need an entire book to grasp these concepts.

Ultimately, unless you have a history of eating disorders, this book is unlikely to harm you—it will just cost you some money and time. I’ve already explained the core framework, so you can take those concepts and see if they help with a routine in your own life.

Frankly, I dislike these lazy “books” that are essentially extended blog posts, lacking rigorous research and relying on anecdotal evidence. They treat readers as if they aren’t intelligent, and I feel my time was wasted for having read it.